As our train named Prospector traveled alongside the seemingly never ending steel water pipeline that delivers water along the 530 km stretch to the Eastern Goldfields from Perth, I am once again reminded of the vastness of Australia, the aridity of this land’s interior, and that how our struggle for fresh water created much conflict since the time of first contact between its original inhabitants and new settlers.

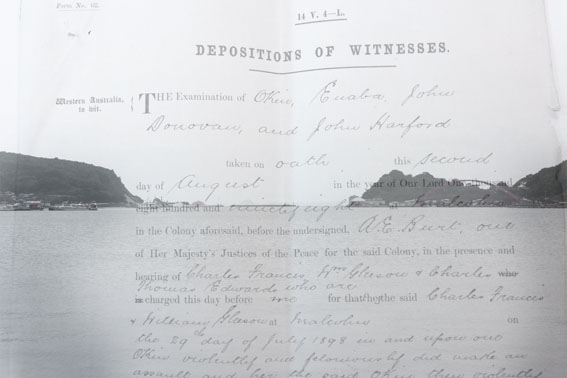

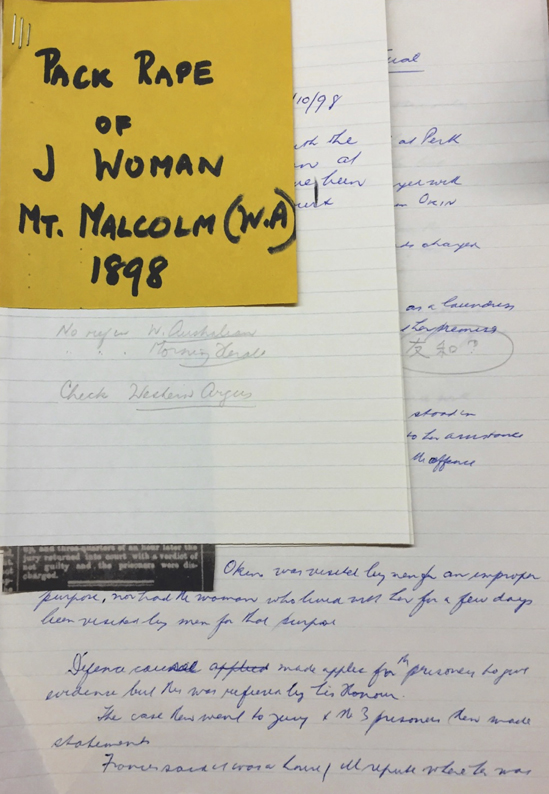

The construction of the Goldfields Water Supply Scheme started in 1898, the same year Okin, a Japanese woman working in the town of Malcolm in the Eastern Goldfields, was allegedly raped. Gold had just been discovered in Malcolm, yet another 230 kms further north from Kalgoorlie into the arid interior of Western Australia.

The thought of how she travelled from her village in Japan with plentiful fresh water from the mountains, what drove her so far into the interior of this dry land, makes me feel ashamed of my air-conditioned comfort. Something about the act of documenting this landscape and my journey to the place Okin had travelled to, lived and worked, with an expensive toy-like video recorder, a GoPro purchased recently especially for this trip makes me feel like a fraud, not to mention the chit chatting with my travel companions, and the sparkling wine from the train kiosk I had been sipping.

My travel companions are both women, both with Australian fathers and mothers from the UK. They had only met that morning for the first time in Perth, when I introduced them as my two long-time friends, who for their own reasons, decided to come along on this journey. Although this was the first time I had companions on a project related research trip, it seemed apt in a loose synchronistic way, considering I originally started this project with a vague idea that I would write about 3 Japanese women in Australian history and their relationships with Australian men, and as a result, my digital parent folder for this project is still labeled “3 Women”.

After hiring a car in Kalgoorlie the following afternoon, we drove up the Goldfields Highway, north to Leonora for the night. Leonora is 19 kms west of, and the nearest town to the now abandoned ghost town site of Malcolm where Okin had once lived and worked in a house she said was a laundry, and others said was a brothel.

Other than the two barmaids, one who was a beautiful young blonde haired ‘Skimpy of the Day,’ dressed in a tight black vinyl g-stringed body suit, the clientele in the main bar of the Leonora White House Hotel were all men. Many worked in nearby mines, others worked on pastoral stations or on road works. I was glad my friends were with me to assist my mission for the night to find local information, especially about the historic town of Butterfly, which used to exist 30 kms south of Malcolm and about the current Butterfly gold mine.

This project has never really had a planned route and destination. All I have really done is to follow signs and gut feelings as it revealed itself in time. The first sign was that I found the results of our 2015 National Opera Review Discussion Paper, which mentioned Puccini’s Madama Butterfly as one of the family favorites in Australian opera as problematic. I applied to the National Library of Australia’s Japan Study Grant (now Asia Study Grant) to research on the history of Japanese women in Australia to find out why. There I found Okin’s story nestled amongst the original manuscripts of historian D.C.S. Sissons, and upon googling the town of Malcolm where she had lived, found the town of Butterfly only 30 kms away. Then I found also through google, that there was a current goldmine called Butterfly too.

I have just been following signs upon signs, coincidences upon coincidences without logic, other than the ones formulated in hindsight, there I was, in the bustling Leonora Whitehouse Hotel with my girlfriends.We decided to go around the bar, buying beers for the men, asking them questions and pumping them for information.